re

:

think

Spring 2014

4

WHEN kung-fu master Bruce Lee hit the

big screen in the 1970s, he did more than

beat up bad guys and astound audiences with

his lightning fast reflexes.

According to Associate Professor Robert

Rinehart from the Faculty of Education’s

Sport and Leisure Studies Department at the

University of Waikato, Lee also empowered

Chinese men, helped develop a Chinese

national identity, bridged Eastern and

Western worldviews and provided a vehicle

to redress social injustices.

Associate Professor Rinehart and

Associate Professor John Wong from

Washington State University collaborated

in a project to analyse Lee’s influence on

martial arts along with the effect his physical

prowess and pride in his body had on a sense

of national identity in China at a time when

relations between China and the west were at

a critical point in history.

Their work, first published in Sports

History Review in November 2013, explains

how Lee – who died in 1973 aged just 32

– made just five movies as an adult but

they played a significant role in raising the

awareness and appreciation of martial arts

throughout the Western world.

The movies also radically changed the

entrenched – and stereotypical – view of

Asian men as either weak and insignificant

or sinister. “One of the ways Bruce Lee tried

to reflect change positively ... is through

the use of his body image,” they say. "Lee

deliberately used his powerful body to

reflect a stronger image of the Chinese male

– and he did it through popular culture,"

says Dr Rinehart.

The pair analysed Lee’s first three movies,

The Big Boss,

Fist of Fury

and

Way of the

Dragon

and found Lee’s contribution to the

construction of national identity was based

on the male Chinese body. He understood

how his body image was able to have a

positive impact on Chinese people both in

Hong Kong and other countries.

Dr Rinehart says his co-author Dr Wong

grew up in Hong Kong in the 1970s. Dr

Wong had the idea for looking at Bruce Lee's

work in terms of the so-called rapprochement

of the East and the West, having watched

the movies when they first came out and

recognising their impact on popular culture.

In the movies, Lee “portrayed a new

conception of the male (Chinese) body and

physical prowess to Chinese, but also to

North American audiences”.

He was able to combine both Eastern

andWestern worldviews, providing a cultural

bridge that served to increase both Western

and Eastern audiences – but also to create

shared understandings between two widely-

diverse cultures.

“Lee consciously worked to create a sense

of pride and, through the action sequences,

his films work holistically to balance the

physical with the cognitive or spiritual.”

They say Lee saw the media – and movies

in particular – as a good way to spread the

word about martial arts and to overcome

stereotypes. While the movie plots were

“fairly formulaic”, it was Lee’s physical

prowess that captivated audiences and

made inroads to “a new perception of

Chinese identity”.

Drs Rinehart and Wong claim Lee, like

most successful actors, “tacitly understood

his relationship to audience and his ‘power’

to embody something more than simply a

singular actor for the cameras”.

At the time, US-China diplomacy

was still in its infancy and Lee offered the

physical embodiment of Chinese strength

and pride, but it came with a Western

connection, making it more palatable to a

Western audience.

It was Lee’s work that opened the way for

“less stereotypical opportunities” for other

Asian actors, such as Jacky Chan and Jet Li.

“In three popular films, Lee’s impact was

great and there are still cults surrounding Lee

that celebrate his impact upon the raising

the status of Hong Kong and Chinese

nationals and émigrés throughout the

world,” Dr Rinehart says.

Assessing the Dragon

Knowing how people learn

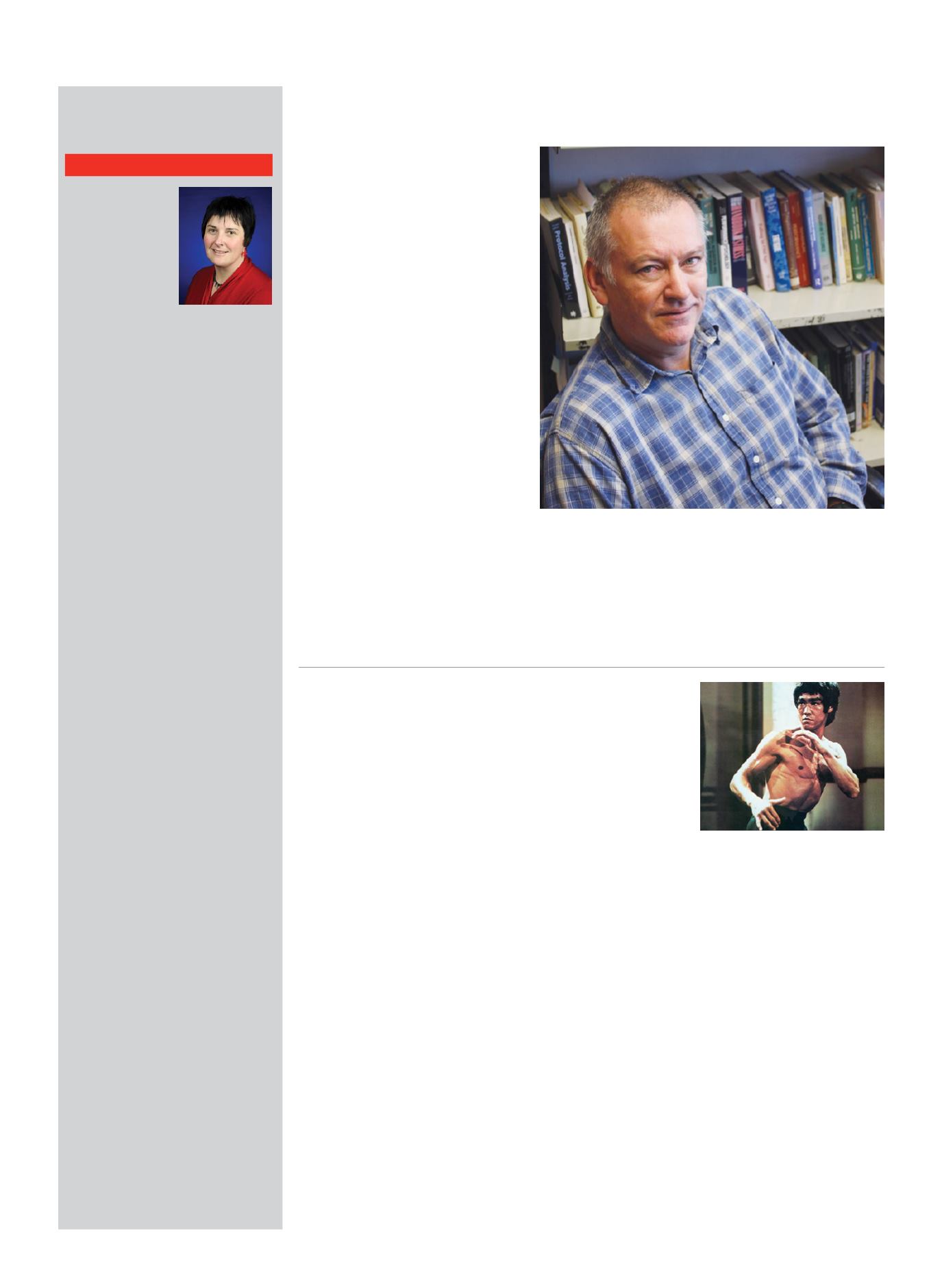

THINK how it’s possible to hit a golf ball perfectly,

until you start thinking about it. Sure as eggs, the

next shot will be a shocker.

“That’s caused by having too much access to

explicit knowledge about your movements,” says

Professor Rich Masters. “But what if you learnt

without that knowledge?”

Professor Masters is an expert in the ways people

learn and perform skills, with his research focusing

on implicit motor learning, the acquisition of skills

without conscious awareness of the knowledge that

underpins their performance.

As the acknowledged leader in implicit motor

learning, Professor Masters says it’s a far more diverse

field than simply sports.

“It has relevance for many different domains in

which movement is important,” he says.

His work crosses discipline boundaries from

sports sciences to rehabilitation, surgery, speech

sciences, movement disorders, ageing, psychology

and developmental disorders and disabilities.

“It’s a fascinating topic that has significance for a

range of interests that are central to the New Zealand

way of life, one of which is high performance sport.

“I’m an experimental psychologist so I design

experiments based on psychological principles to

examine the way people learn and perform skills.”

Professor Masters is based in the Department

of Sport and Leisure Studies in the Faculty of

Education at the University of Waikato, returning

to New Zealand after 13 years in Hong Kong, where

he was first Assistant Director then Director of the

Institute of Human Performance at the University of

Hong Kong. Before that he lectured in the School

of Sport and Exercise Sciences at the University

of Birmingham.

He’s returned to New Zealand to give his

family a Kiwi lifestyle and is impressed with his

new surroundings.

“This department at Waikato University wants

to go places. It’s interested in research, and wants to

strengthen its appeal to undergraduates by offering

something unique in New Zealand,” he says. “That’s

where I come in.”

AS I sat watching the

Commonwealth Games

I reflected on what such

events mean in the

hearts and minds of our

tamariki (children).

How many are

inspired to strive for the

glories – and the often

forgotten heartbreaks –

that elite athletes experience, especially when a gold

medal is hung around their necks and the national

anthem plays?

There is no doubt in my mind that such

achievements should be recognised and celebrated,

and the athletes and their support teams be

acknowledged for their persistence and dedication.

But standing on the sidelines of children’s sport in

schools, clubs and at representative level, sometimes

you might be fooled into thinking you too were in a

Commonwealth Games venue, as the endeavours of

the thousands of tamariki who engage in sport after

school and on Saturday mornings are presented as if

they are competing on the world stage.

You would think that many provincial primary

school-aged representative teams were heading to a

World Cup, not a national under-13 tournament.

It’s not the tamariki who make it such, it is the

parents and coaching staff who forget that it is

children’s sport, a place for children to learn about the

joy found in movement, to develop interpersonal and

self-management skills, to have fun, to make friends,

to explore, and experience the challenge of competing

against themselves and amongst others.

Instead we see cross-fit for pre-schoolers,

soccer and netball for tots, elite sports camps

for intermediate-aged children, tamaiti (child)

specialising in a particular sport before they have got

to high school, and thousands of dollars a year spent

on making sure your precious ‘elite’ tamaiti has all the

‘necessary’ equipment and coaching to give them the

best chance of achieving their dream (or should that

be their parents’ dream?).

We seem to be more and more fixated on

creating mini-adults, by training them in adult ways

and neglecting to keep it all in perspective.

When you are a world BMX champion at eight

years old, what does the future look like? Will he/she

be an Olympian, a Commonwealth Games athlete

or still be a world champion as an adult? Will they

be finely tuned athletes or physically and mentally

burnt out?

Will they be crippled not only by the chronic

injuries they picked up as an age group ‘elite’ athlete,

but also by the mental and social scars associated

with failing to maintain a world ranking or from the

missed opportunity to be a kid?

My hope is for a future where all tamariki have

opportunities to engage in multiple movement

activities (not just formalised sport) where they

experience the joy found in effort, pleasure in

moving, inclusive and supportive play and learning

environments, and success that is meaningful for them

and not determined by narrowly defined concepts

of what counts. For this to happen means parents,

coaches and administrators will need to rethink what

matters most when it comes to sport and other

movement experiences for children and youth.

- Dr Kirsten Petrie is the chairperson of the Sport

and Leisure Studies Department in the Faculty of

Education at the University of Waikato.

Let the children play-

It's not the world cup

COMMENT

DR KIRSTEN PETRIE

BY DR KIRSTEN PETRIE

BRUCE LEE: Empowered Chinese men.

DON'T THINK SO

HARD: Professor

Rich Masters, a

leader in implicit

motor learning.